Most sheltered veterans experience homelessness as individuals, rather than as part of a family unit.

A count of people experiencing homelessness in communities across America revealed that veterans, who make up less than 8 percent of the total U.S. population, represented roughly 16 percent of adults experiencing homelessness on a single night in January 2009. Of the 75,609 homeless veterans counted that night, more than half were living in emergency shelters or transitional housing; the others lived on the street, in abandoned buildings, or in other places not meant for human habitation. Annual estimates are derived from Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) data, which are administrative databases designed to record and store client-level information on the characteristics and service needs of homeless persons. In 2009, 300 communities across the country submitted HMIS data to HUD, revealing that between October 1, 2008 and September 30, 2009, 136,334 veterans spent at least one night in emergency shelters or transitional housing facilities.

A 2010 U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness report, Opening Doors: Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness, sets a goal of ending homelessness among veterans within five years. Reaching this goal requires an understanding of the scope and nature of veteran homelessness. HUD’s Office of Community Planning and Development annually releases a homeless assessment report to Congress to share national findings from HMIS, Point-in-Time counts, and other data. This year, for the first time, HUD coordinated with the Department of Veterans Affairs to expand the understanding of this subpopulation with Veteran Homelessness: A Supplemental Report to the 2009 Annual Homeless Assessment Report. The report helps inform questions about whether some veterans are at greater risk of homelessness than others are, who and where the veterans living in residential homeless facilities are, and how homeless veterans use the shelter system. The 2010 Annual Homeless Assessment Report was published in June 2011, and the 2010 supplemental report on veterans is expected to be released in summer 2011.

Veterans who use shelters are located mostly in large cities, while half are in the states of California, Texas, Florida, and New York.

Veterans at Risk of Homelessness

To explore whether some types of veterans are especially at risk of becoming homeless, the rates of homelessness among individual veterans were compared with homelessness rates of the total U.S. adult population, all poor adults, all adult nonveterans, and all poor nonveterans. These comparisons indicate that:

-

Female veterans are at greater risk of homelessness than male veterans and are two to three times more likely to be homeless than any of the comparison groups.

-

Rates of homelessness are higher for Hispanic, African American, and Native American veterans than for nonminority veterans, especially among those who are poor.

-

Veterans between the ages of 18 and 30 are twice as likely as adults in the general population to be homeless, and the risk of homelessness increases significantly among young veterans who are poor.

Female veterans in families are at higher risk of becoming homeless, whereas homeless male veterans in families are underrepresented when compared with other populations. The risk of homelessness for veterans in families across all racial and ethnic groups is low and suggests that being part of a family, even when poor, may be a safeguard against homelessness.

About Sheltered Homeless Veterans

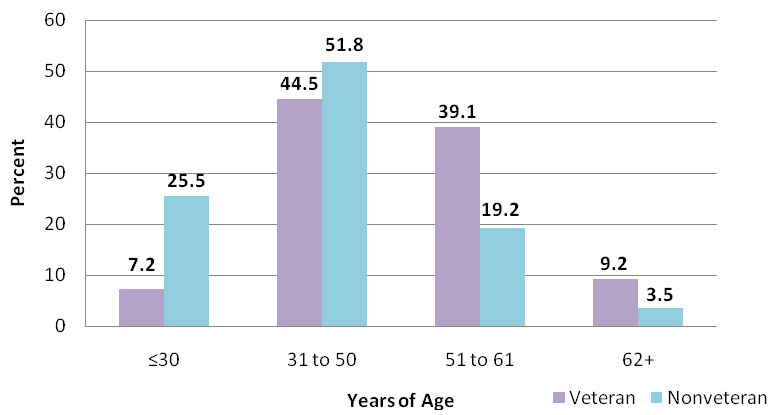

Based on 2009 HMIS data, sheltered veterans are typically male, equally likely to be minority or white non-Hispanic/non-Latino, between 31 and 50 years old, and disabled. However, the demographic profile of the typical sheltered homeless veteran depends on the composition of the veteran’s household. Most sheltered veterans (97%) experience homelessness as individuals; only a small number (3%) are part of a family unit. The typical sheltered veteran accompanied by a family is female, African American, between the ages of 31 and 50, and not disabled.

Figure 1. Age of Sheltered Homeless Individual Veterans and Nonveterans, 2009

Source: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans. Veteran Homelessness: A Supplemental Report to the 2009 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, 13.

Geographically, the distribution of the sheltered veteran homeless population is similar to sheltered nonveterans; most are in principal cities and half are in California, Texas, Florida, and New York. Veterans utilizing shelter in principal cities are frequently local, in that their last permanent zip code was in the same area in which they first accessed residential services during the 12-month reporting period.

Use of the Shelter System

HMIS data captures the point of entry into the homeless assistance system, which can be useful information when developing interventions. Asked where they had stayed the night before entering emergency shelter or transitional housing, many veterans (46%) were already homeless, having come from another shelter or an unsheltered living situation, such as the street. Thirty-two percent had stayed in their own home or with family or friends, 14 percent came from institutional settings, and 8 percent came into the system from other situations.

Sheltered veterans followed a nonlinear pattern of using homeless services during the 12-month window from October 1, 2008 to September 30, 2009, meaning that they did not proceed from emergency shelter to transitional housing to permanent housing. During this period, HMIS data indicated that 76 percent of the homeless veterans who accessed residential services only used emergency shelters. Another 19 percent lived in transitional housing, and approximately 5 percent used both types of shelter. The cumulative length of stay for the year was usually brief. A third of homeless veterans stayed in emergency shelters for less than a week; 61 percent were there less than a month, and 84 percent stayed for less than 3 months. Transitional housing stays tended to be longer, ranging from one to nine months for most residents.

These and other data in the report describe the population of homeless veterans in detail and serve as a baseline for monitoring homelessness among veterans. This information supports federal interagency collaboration to end homelessness among veterans and allows researchers to track changes in homelessness among veterans over time and measure progress toward eradication.

BACK TO THE TOP

LEED project under construction by Hudson Companies, who uses energy modeling to identify needed design improvements.

Built for elderly and disabled persons, Section 202 and Section 811 units have been part of HUD’s assisted housing stock for nearly 50 years. No single description fits the existing inventory of 288,000 units. Although most were built within the past 20 years, some date back as early as the 1960s. They take the form of duplexes, single-family homes, row or townhouses, low-rise and garden apartments, and mid- to high-rise apartments. They are found in every region of the country, with the heaviest concentrations in the South.

As part of an initiative to make HUD-supported projects more energy-efficient and sustainable, in 2011 HUD instituted new energy usage and water conservation requirements for Section 202 and Section 811 units. HUD also encourages developers to incorporate other green building design and features in their projects. To support these efforts, HUD’s Office of Policy Development and Research devotes a section of a new report on energy efficiency and green building techniques to strategies applied “in the field” by owners and sponsors. Researchers conducted case studies of five organizations’ activities to identify key strategies and practices, which include data analysis, implementation approaches, standards selection, leveraging of additional funds, and resident education.

Strategies Informed by Data

All five organizations put data to work through energy modeling, audits, benchmarking, and/or utility bill management. Energy modeling is a computer-based tool that predicts energy usage for a base design over a certain period of time, and then compares it to the predicted usage of different energy-saving designs. Building location, envelope, systems, loads, and schedules are among the factors considered. The results of energy modeling help determine which energy efficiency measures to adopt in new construction or substantial rehabilitation of units. The Hudson Companies, Inc. in Hermitage, Pennsylvania uses energy modeling to identify needed design improvements to HVAC systems, windows, building envelope, plumbing, and lighting when finalizing the design of new construction projects. Neustra Comunidad Development Corporation (CDC) uses energy modeling to determine anticipated costs, savings, and payback periods.

Energy audits assess the amount of energy used in an existing building and project the effects of rehabilitation. These audits identify areas of the building where energy is lost or used inefficiently. The information enables owners to make modifications and prioritize energy-efficiency measures. Audits are sometimes combined with energy benchmarking techniques. New Ecology, Inc. (NEI), a nonprofit that offers consulting services to Section 202 projects, assesses current utility usage and costs with its own online benchmarking tool, which compares an existing building’s energy consumption with that of similar buildings. With information about a building and its utility accounts in hand, the tool automatically downloads the property’s energy use data from the utility company. If the analysis suggests poor energy performance, an audit can pinpoint the problem. NEI finds that energy audits can lead to a 20- to 30-percent reduction in energy use. The cost savings are enough to offset the total expenses of the front-end utility analysis, energy audit, and energy-efficiency upgrades.

Utility bill management in existing housing units also reduces energy costs. In this approach, savings are generated by identifying and eliminating rate error, meter inaccuracy, water leakage, meter-reading error, and late fees. National Church Residences (NCR), manager of a large portfolio of Section 202 properties, has achieved significant savings by centralizing utility data management. NCR processes all utility bills for its 258 properties at an annual cost of $75,000; annual savings total $220,000. The data collected also allow NCR to benchmark its projects, pinpoint the most needed energy retrofits, and make energy-efficiency improvements routine.

Green roof of a Section 202 property in development by Nuestra CDC, who trains staff and residents to recognize maintenance and repair needs of energy-efficient features in their buildings.

Other Strategies: Implementation, Standards, Funding, Education

Section 202 and Section 811 property owners/sponsors choose different methods for incorporating energy efficiency and green features in their developments. One strategy is to concentrate on one component of a property at a time, such as a lighting retrofit in all common areas. Other strategies use a project-by-project approach, or one in which a selected energy-efficiency or green building standard — such as ENERGY STAR® appliances — is applied across an entire property portfolio.

Some owners or sponsors subscribe to a program that makes green and energy-efficiency standards prerequisite to certification. If a set of standards meshes with an organization’s objectives, if financial resources are available, and if there is sufficient staff expertise, building to certification standards can be advantageous.

Financing energy-efficiency and green building measures often requires additional funds beyond Section 202 and Section 811 monies. REACH Community Development seeks small and large grants to cover energy-efficiency and green measures. In its first Section 811 project, with 19 units for persons with mental health and substance abuse problems, REACH installed compact fluorescent light bulbs throughout the project using local weatherization assistance funds for low-income households. HUD’s Green Retrofit program supplied funds for new hot water heaters and exterior doors, greener countertops and floor coverings, a drip irrigation system, and a solar photovoltaic system with roof replacement. A grant from the Oregon Housing Acquisition Project will replace packaged terminal air conditioner units with ENERGY STAR-qualified units, and REACH is applying for funds to replace toilets with energy-efficient models.

Finally, residents and maintenance personnel have a critical role to play in reducing energy consumption, not only by practicing energy conservation, but also by learning how to use energy-efficient features and recognizing problems that require maintenance. Nuestra CDC trains its staff in proper operation, maintenance, and repair. In turn, managers and maintenance staff educate residents, both formally and informally, as to why features are added, how they work, and how they affect the tenants’ homes.

BACK TO THE TOP

Paul Emrath and Heather Taylor of the National Association of Home Builders presented "Housing Value, Costs, and Measures of Physical Adequacy" at the inaugural American Housing Survey (AHS) User Conference in March 2011, hosted by HUD’s Office of Policy Development and Research. The study explored an alternative to the traditional criteria used in measuring physical housing inadequacy with AHS data. Traditionally, housing inadequacy has been defined as moderate or severe according to the conditions shown in Tables 1a and 1b.

|

1. At least 3 of the following:

Outside water leaks;

Inside water leaks;

Holes in the floor;

Open cracks in inside walls or ceilings;

Area of peeling paint larger than 8” x 11”;

Recent rat sightings.

2. More than 2 toilet breakdowns of over 6 hours.

3. Main heating equipment is unvented room heaters.

4. Lack of complete kitchen facilities.

|

|

|

1. At least 5 of the conditions in Table 1a(1).

2. Fewer than 2 full bathrooms without hot and cold running water, or without bathtub or shower, or without a flush toilet, or with shared plumbing.

3. Respondent reports being cold for 24+ hours and at least 2 breakdowns of heating equipment that lasted longer than 6 hours.

4. Respondent reports that household does not use electricity.

5. Exposed wiring, plus a lack of electrical outlets in every room, plus fuses that have blown more than twice.

|

|

New Measure Drawn from AHS

Emrath and Taylor developed a measure based on housing characteristics reported in the AHS that negatively affect the value of owner-occupied housing and lower the rents for renter-occupied housing units. The proposed model incorporates two sets of characteristics: one for single-family structures, emphasizing exterior structure issues, and one for multifamily housing units, which focuses on interior integrity and functionality.

Findings

Attendees of the AHS Users Conference weigh the utility of an alternative method for measuring physical housing inadequacy.Emrath and Taylor found that, unlike the traditional measures of housing inadequacy noted in the tables above, their model yields statistically significant results. Physical inadequacies in single-family housing with a significant negative effect on value included: missing siding; broken windows; holes, cracks, or crumbling in the foundation; sagging roof; and holes in the roof. Physical inadequacies in multifamily housing with a strong depressive effect on rent levels included: lack of a kitchen sink, no bathroom sink, open cracks in the interior walls or ceilings, a breakdown of the sewage system since the last interview, and a lack of built-in equipment that distributes heat throughout the unit in climates with 4,000 or more heating degree days.

Significant discrepancies in estimates exist between the old and new measures. The new measure identified a larger number of physically inadequate housing units, especially single-family units (see table 2). Using the traditional inadequacy standards with the 2009 AHS data, approximately 2.7 million single-family (3.5%) and 2.6 million multifamily (10.1%), structures are moderately or severely inadequate, whereas the alternative measure resulted in 6.7 million single-family (8.5%) and 2.1 million multifamily (8.3%) inadequate occupied housing units. The alternative measure also identifies 1.5 million inadequate units among nonseasonal vacant housing units that are outside the scope of the traditional standards.

|

Table 2. Number of Inadequate Housing Units under Alternative Definitions

|

| |

Occupied

Single Family |

Multifamily |

Vacant Nonseasonal

Single Family |

Multifamily |

Total |

| AHS Severely Inadequate |

991,358

1.3% |

744,606

2.9% |

— |

— |

1,735,965

1.5% |

| AHS Moderately or Severely Inadequate |

2,777,494

3.5% |

2,607,392

10.1% |

— |

— |

5,334,886

4.6% |

| Inadequate Under New Definition |

6,733,007

8.5% |

2,153,890

8.3% |

1,104,633

19.4% |

397,619

8.9% |

10,389,149

9.0% |

| Total Housing Units |

79,133,307 |

25,920,344 |

5,707,567 |

4,449,398 |

115,210,615 |

|

|

Source: Emrath and Taylor, “Housing Value, Costs, and Measures of Physical Adequacy,” presented at American Housing Survey User Conference, March 8, 2011, p. 25.

|

More Findings: About Inadequate Units

Using their new model and definition, Emrath and Taylor identified other information about inadequate housing units. Available from the American Housing Survey, information about physically inadequate units is potentially useful for local and national planning, policymaking, market response, and for further research. These additional findings include the following:

-

Inadequate units identified by the new measure are concentrated in older housing stock and geographic areas.

-

A particularly high rate of inadequacy (19%) in nonseasonal vacant single-family housing suggests that many units on the market may be difficult to sell or rent without substantial repairs or upgrades.

-

Housing inadequacy affects more owners (5.2 million) than renters (3.7 million).

-

Nearly 40 percent of renters in inadequate housing are at the lower end of the income distribution, earning less than 30 percent of the area median income. Owners with inadequate units, on the other hand, are spread evenly across the income distribution and may lack knowledge about a structure’s maintenance and repair requirements.

-

When examining the distribution of inadequate housing across race and ethnicity, researchers found one overrepresented group — non-Hispanic black homeowners.

-

Families with children under 18 were also overrepresented, particularly those headed by single parents and other nonmarrieds. These families accounted for just 6.7 percent of all homeowners but 11.6 percent of owners in inadequate housing. Likewise, they account for 19.7 percent of all renters, but 26.1 percent of renters in inadequate units.

BACK TO THE TOP

[T]ransit in most metro areas still concentrates primarily in cities, and provides hub-and-spoke rail service misaligned with the suburbanization of employment and people.1 — Tomer, et al., “Missed Opportunity: Transit and Jobs in Metropolitan America”

In areas with transit service, the median time between transit stops is 10.1 minutes during morning rush hour. Credit: California Department of Transportation.

How well do public transit systems connect people with jobs? Researchers at The Brookings Institution investigated this issue by compiling detailed information about public transportation in the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas and combining it with demographic and employment data to develop measures of coverage, service frequency, and job access.

Although differences in geography, growth policies, and regulations create widely varying levels of transit coverage in these metro areas, some of the findings from Missed Opportunity: Transit and Jobs in Metropolitan America were common to most locations. In general, although more than two-thirds of working-age residents and most of the poor now live in suburbs, only 58 percent of suburban neighborhoods are served by transit. In areas that do have transit service, the median time between transit stops during the morning rush hour is 10.1 minutes, with less frequent service in suburban neighborhoods. In addition, 70 percent of available jobs cannot be reached within 90 minutes by public transit.

Researchers found that the problem is exacerbated by a mismatch between the types of jobs available and the skill levels of typical workers who can get to those jobs in a reasonable time:

[T]he typical working-age person in neighborhoods served by transit can reach one-third of metro area jobs in high-skill industries within 90 minutes of travel time, compared to just over one-quarter of metro area jobs in middle- or low-skill industries (18).

The hub-and-spoke design of traditional transit systems hinders job access for suburban residents. Whereas city residents can reach 46 and 36 percent of high- and low-/middle-skill jobs, respectively, within 90 minutes by transit, those numbers are 24 and 19 percent, respectively, for suburbanites. The study finds that residents of low-income suburban neighborhoods are able to reach only slightly more than one-fifth of the low- and middle-skill jobs for which they are most likely qualified.

The study reports transit coverage, service frequency, and job access findings for all 100 large metropolitan areas. The study also ranks these metro areas based on the share of the working population served by transit and the share of jobs reachable within a 90-minute commute. As communities face severe budgetary and program challenges, this study can be helpful in forging strategic connections between people and jobs that support and grow local economies.

1 Adie Tomer, Elizabeth Kneebone, Robert Puentes, and Alan Berube, "Missed Opportunity: Transit and Jobs in Metropolitan America," Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings Institution, May 2011.

BACK TO THE TOP

|