|

Crane installation of a HUD-Code home.

Manufactured housing built under HUD standards offers clear cost advantages over conventionally built housing, and so could be a significant source of housing to low-income and workforce families in the United States. Despite the affordability advantages of manufactured housing, this housing has had no discernible impact in meeting the affordable housing needs of urban areas. One explanation rests in local and state regulations that hinder the acceptance of manufactured housing as a viable housing option. “Regrettably,” Assistant Secretary of Policy Development & Research (PD&R) Raphael Bostic observes, “when these policies or practices restrict the development of affordable housing in communities, such policies and practices become regulatory barriers that restrict the opportunity of hard-working American families to live in the communities where they work or where they would like to live.”1

The Center for Housing Research completed a study for HUD’s Office of PD&R that investigates the role of state and local regulatory practices in constraining manufactured home placement in urban communities. The Center analyzed the content of state and local regulations as they influence the supply and placement of manufactured housing in local communities and completed four case studies in communities that have had successes and challenges in regulatory reform and placement of manufactured housing.

State Legislative Treatment

Investigating how states legislatively treat manufactured housing, the Center found that 40 states and the District of Columbia regulate manufactured housing in some manner. Most of these states define manufactured housing as any that meets HUD standards (HUD-Code); some also qualify their definition by minimum square footage, placement on a foundation, architectural features, etc. Thirty-one states define manufactured housing as real property, which allows homeowners to qualify for mortgage financing and the same tax deductions accorded to other residential owners. A little more than half of all states require that local jurisdictions allow HUD-Code units, but most say nothing about additional local requirements concerning design, installation, lot improvements, and placement on site.

The Center further constructed an Inclusion Index that measured the extent to which states encourage localities to include manufactured housing, finding that 15 were weak, 15 were moderate, and 21 were strong, statutorily. When Inclusion Index results were compared to shipment patterns between 2000 and 2005, it was apparent that states that strongly encourage manufactured housing received significantly more shipments of manufactured housing.

Local Regulatory Climate

The local regulatory state of affairs was assessed with a survey of about 800 CDBG-eligibile jurisdictions. A majority (59.4%) had new HUD-Code units and 17 percent had approved new mobile home parks, communities, or subdivisions in the past 5 years. Queried about placement regulations, nearly 40 percent of these jurisdictions restrict the units to special zoning categories like mobile home parks, while 20 percent allow special or conditional permits for HUD-Code homes in single-family zones. A majority allow manufactured homes as a by-right use in single-family zones, either under the same rules as other housing or with special design standards. When asked to rate a list of potential barriers to HUD-Code homes, only a few respondents thought any of the items prevented the placement of manufactured homes in their communities. Items most often selected (but still by a minority) as a significant barrier included high land cost, citizen opposition, no new parks, zoning codes, and not much land. Items like fees, permits, wind codes, snow load standards, fire codes, and environmental regulations were generally not perceived as barriers, but the researchers found that these items do reduce the probability that a unit will be placed in a community.

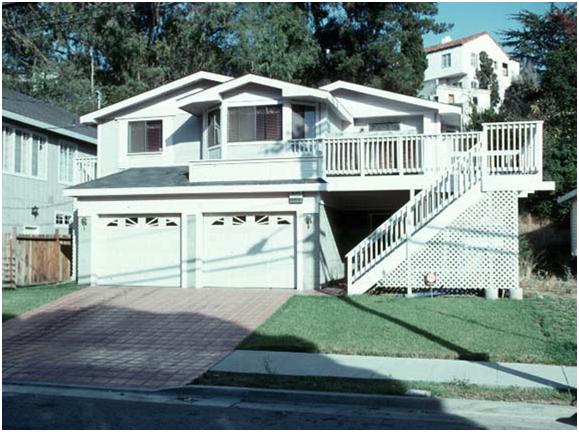

A tri-section configuration demonstrates the flexibility of manufactured housing for infill units in urban areas.

If units are allowed in local communities, market barriers seem to have a greater role in placement, while regulatory barriers are associated more with whether jurisdictions have any HUD-Code units at all. As for numbers of placements made, the number of units placed was higher where new manufactured housing parks or subdivisions were approved. Localities with the highest numbers of placements effectively balanced placements between parks and traditional subdivisions (as infill or alternative to site-built homes). Communities that promoted placement with special incentives were much more likely to have placed over 50 units in the past 5 years.

In addition to using survey data and statistical models to identify factors that influence the use of manufactured housing, the Center completed four qualitative case studies. Three of the localities studied have successfully used manufactured housing in urban infill (Oakland, CA); subdivisions of manufactured housing (Washington state); or placements in high-growth, expanding suburbs (Pima County, AZ). Owensboro, KY exemplifies the challenges of developing and marketing manufactured housing in a state where manufactured housing receives legislative support and is used prevalently in rural areas. In these case studies, nonprofit affordable housing organizations were influential in promoting the use of manufactured housing. Important lessons gleaned from the experiences of these four communities suggest that local market conditions and competitive advantages, along with the support of financial institutions, have a lot to do with how well manufactured housing is utilized. Regulatory reform enables, but on its own, is not a sufficient condition to promote wider use of manufactured housing.

1 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research, Foreword to Regulatory Barriers to Manufactured Housing Placement in Urban Communities, 2011.

BACK TO THE TOP

Pioneering households that relocate to a lower income neighborhood are more likely to be renters, first-time homeowners, childless couples, and minorities.

The inaugural American Housing Survey (AHS) Users Conference in March 2011 provided researchers with an opportunity to explore innovative uses of AHS data. Presenters Ingrid Gould Ellen, Keren Horn, and Katherine O’Regan used data on recent occupants from the AHS and neighborhood data from the decennial census to explore pioneering residential decisions in which higher income households choose lower income neighborhoods.

These researchers define pioneering households as households that move to homes whose previous occupants earned incomes of at least 5 percent less than their own, that have incomes of at least 40 percent of the area median income, and that are in neighborhoods with incomes below the median for the metropolitan statistical area. Compared with nonpioneers, pioneering households are more likely to be minorities, renters or new homeowners, younger, and childless.

Using AHS data to learn why these new occupants chose a neighborhood, the researchers completed a series of regression analyses for all households and for homeowners and renters, separately. They found that pioneering moves are more likely in metropolitan areas with lower crime rates, where such moves are less risky. These moves are also more likely to occur in metropolitan areas with rapidly accelerating home prices, where first-time homeowners and renters may be constrained by housing costs. For minorities, pioneering is higher in more segregated metropolitan areas, where their housing options may be even more constrained.

Ellen, Horn, and O’Regan also found evidence that pioneering households exhibit different residential choice preferences than nonpioneers. Through residential choice models, the research shows that pioneers place different weights on observable neighborhood characteristics, particularly older housing stock. Specifically, neighborhood aesthetics and public schools are less important to pioneers than proximity to family and friends, unit characteristics, and financial considerations. The research also reveals that pioneers report lower commute times than nonpioneers, although a centrally located neighborhood does not appear to be a preference.

Overall, pioneering households live in older homes, have shorter commutes, save money on housing costs, and are more likely to have heard about their chosen unit from friends. Finally, the stated motivations and preferences of pioneer households are consistent with an increased emphasis on unit quality and housing costs and reduced emphasis on neighborhood amenities.

BACK TO THE TOP

Hurricanes Katrina and Rita displaced more than 1 million people when they hit the Gulf Coast in 2005, and caused widespread destruction to lives, communities, and property. That year, to help residents rebuild, Congress allocated $19.7 billion in supplemental Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) funds for disaster relief, 99 percent of which went to Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. The states, in turn, allotted the bulk of those funds to devastated homeowners.

Example of property in poor condition.

Nearly five and a half years after the storms, HUD’s Office of Policy Development & Research has issued a report on Phase I of a two-part assessment of efforts to rebuild housing in the most heavily damaged areas of those three states. The study also evaluates the role that CDBG funds have played in these recovery efforts. Its goal is to assess how to more effectively implement and use CDBG funds for disaster relief in the future.

On the Ground Assessments

From January to March 2010, trained observers assessed a representative sample of housing on 230 “severely affected blocks” in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. Observers looked for damage visible from the street (so-called “windshield” observation), like missing or broken windows and doors, sagging roofs, and flood line.1,2,3 They also looked for evidence of ongoing repair, and whether the structures were inhabited. In order to figure out how much rebuilding had taken place, researchers compared their findings with Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA’s) initial damage assessments.

The study estimates that among residential properties in the most-battered areas in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas:

-

About three-quarters (74.6 percent) of properties damaged by the storms are in good condition.

-

59 percent of blocks have been “substantially rebuilt.”

-

Properties most in need of repair are clustered in neighborhoods with fewer resources, where home values, incomes, and rates of occupancy and homeownership are lower. Specifically, Biloxi, Mississippi, and the Louisiana parishes Lower Ninth Ward, MidCity, and ByWater have rebuilding rates of less than 50 percent.

-

10.8 percent of properties lack a permanent residential structure. In other words, an empty lot or FEMA trailer stands where, in 2005, housing stood.

-

14.6 percent of properties still have a structure with substantial repair needs.

-

Public infrastructure is still in need of work; 38 percent of severely affected blocks across the 3 states showed damage to roads, fire hydrants, signage, and electrical lines, and only 6 percent showed ongoing repair.

-

When controlling for income and the extent of damage, neighborhoods with greater proportions of black and Latino populations have made more rebuilding progress.

Finally, based on their observations, researchers believe that less than four percent of affected properties are actively being repaired or rebuilt.

a The condition of the structure could not be assessed because it was under construction or undergoing major renovation.

CDBG Administrative Data

CDBG funds were available both to homeowners and landlords with small (one to four unit) rental properties. The funds were meant to fill the gap between other compensation devastated property owners received (private insurance, FEMA grants, etc.) and the total damage assessed on a property. By pairing CDBG data with field observations, the study showed that, when adjusted for county- and neighborhood-specific differences, CDBG awardees are more likely to have rebuilt and reoccupied housing than those who did not receive a grant.

The study also shows that Mississippi homeowners who received CDBG grants were much more likely to have their needs fully met than homeowners in Louisiana who received CDBG grants, based on a comparison of total assistance — including CDBG, private insurance, and other funds — to assessed damage. Some 66 percent of Mississippians who received CDBG funds obtained assistance that equaled 100 percent of the assessed damage. But in Louisiana, only 35 percent of CDBG recipients had received funds totaling 100 percent of the assessed damage. However, this may be due largely to different methods of damage assessment.

Phase II

In the second phase of this study, the plan is to interview owners (in 2005) of residential buildings to better understand why they have or have not rebuilt, and to assess the scope of damage inside properties. Doing so will enable researchers to further evaluate how the availability of CDBG funding has affected Gulf Coast housing recovery.

1 3,511 properties were assessed during this study; FEMA assessed a total of 312,463 properties in the few months after the storm.

2 FEMA categorized “severely affected blocks” as Census blocks that contained three or more properties that sustained major or severe damage.

3 These observations do not include internal damage, such as flooding or mold, or problems to the foundations or roof not visible from the street.

BACK TO THE TOP

- HUD USER’s new events page. This page highlights quarterly briefings on recent market conditions data and current research; HUD’s newsletter, Insights, that highlights research on key housing and community development topics; and materials from recent conferences, including the 2011 AHS USER and Neighborhoods of Choice and Opportunity (HOPE VI) conferences.

- The Urban Land Institute’s Robert C. Larson Workforce Housing Public Policy Awards program, which recognizes innovative public policies and practices for the production, rehabilitation, or preservation of workforce housing. Click here for more information and to download the application.

BACK TO THE TOP

|