The Case for Small Home Design as a Component of Sustainability Efforts

Small homes have the potential to use less energy and offer more affordability than larger homes.

Sustainability, defined by the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs,” has increasingly become a focus of both government policy and private practice. At the 2016 convention of the American Institute of Architects, Michael Fifield, professor of architecture and director of the Housing Specialization Program at the University of Oregon, held a session titled “Smaller Residential Unit Design Principles as a Key to Sustainability,” in which he made the case for including small home design within larger efforts to reform land use patterns for achieving sustainability. According to Fifield, small homes could not only help meet current housing demand generated by demographic shifts but also reduce energy use and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that will help preserve the environment and meet the needs of future generations.

Changing Home and Community Design

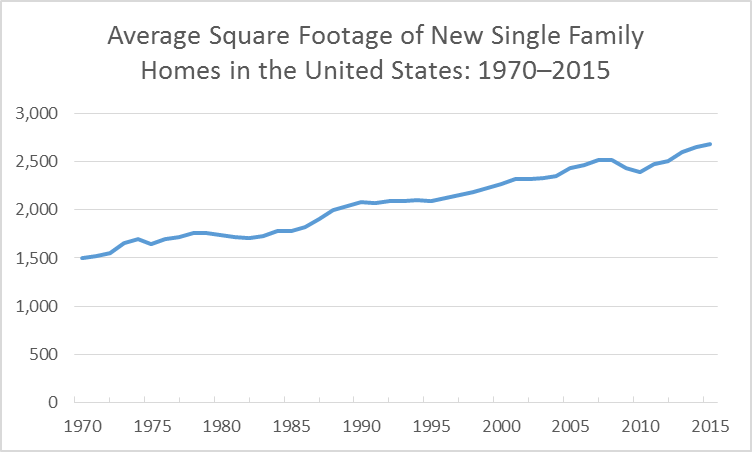

According to Fifield, the typical development pattern in the United States once featured small houses and small lots in a pedestrian-friendly grid pattern. The introduction of the automobile, however, transformed this pattern of development. Over time, home designs began to feature garages, suburban streets became wider, and pedestrian linkages became less necessary. Home sizes also changed, as shown in figure 1. Although micro units, which are studio apartments generally smaller than 350 square feet in size, have recently re-emerged as a housing option in some multifamily structures, new single family homes have increased in size over the last few decades. Between 1970 and 2015, the average size of newly constructed homes increased by 79 percent, from 1,500 to 2,687 square feet.

Figure 1

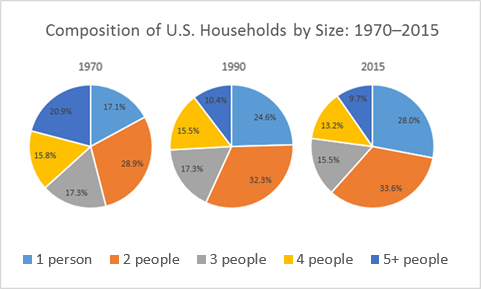

This increase in average home size, however, did not correspond with an increase in household size. Between 1970 and 2015, the percentage of households with five or more members declined from 20.9 percent to 9.7 percent, and the percentage of one-person households increased from 17.1 percent to 28.0 percent (figure 2). The distribution of household types in the United States also changed over time; in 1970, 40.3 percent of all U.S. households were married couples with children, but in 2015, married couples with children only made up 19.3 percent of all households in the nation. During this time, the percentages of men living alone, women living alone, and other nonfamily households increased.

Figure 2

Meeting Current Needs

The ability to meet current housing needs is an important component of efforts to achieve sustainability. The shift in U.S. household composition toward smaller households and the rise in single-person households is driving a need for a more diverse housing stock that includes small homes, which Fifield defines as homes of 1,200 to 1,600 square feet in size. Fifield notes that housing must also meet other needs for most consumers, including privacy, safety, and storage. Consumers also generally desire that housing be affordable; provide adequate space for activities such as eating and sleeping; and be located close to employment centers, recreation opportunities, and retail establishments.

Small homes can meet these needs. Creating small homes on small lots allows for higher-density, more compact development, which reduces sprawl and permits pedestrian access to amenities. Consumer needs and preferences for storage and space for activities can also be met in small homes through careful design. Using spaces for multiple purposes, such designating a room as both a library and a guest room, and better utilizing vertical space — for example, through bunk beds — can help reduce the floor area needed within a home. Installing built-in cabinetry that includes a Murphy bed can allow a room to be used as both a lounge area and a sleeping area at different times. In addition, alcoves can be used to separate functions and provide privacy for activities such as sleeping or eating without requiring as much space as a fully enclosed room.

Design solutions can also ensure adequate household storage through the creative use of existing spaces, such as installing drawers under a bed or installing shelves in the space under stairways, along hallways, or within widened wall framing. Design details such as mirrors, exposed ceiling joists, open floor plans, and layouts that connect indoor and outdoor spaces using windows or outdoor rooms can also make homes feel larger than they are without adding extra square footage.

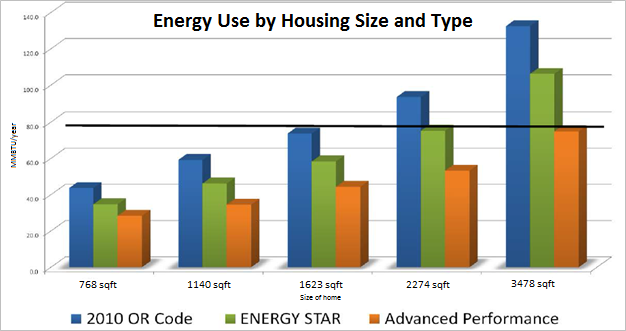

Small homes also have the potential to be more affordable than larger homes, both initially (because they require less land and fewer materials to construct) and over the course of their life cycles (because they are more energy efficient). Small homes may be naturally more energy efficient without the inclusion of green features; according to Fifield, the average 1,623-square-foot house designed to meet Oregon’s standard building code uses the same amount of energy as the average 2,274-square-foot house meeting ENERGY STAR criteria. These statistics highlight the reduction in energy that could be attained by building homes that are both small and energy efficient (figure3).

Figure 3

Credit: Michael Fifield

Allowing Future Generations the Ability To Meet Their Own Needs

In addition to meeting current needs, efforts to achieve sustainability must provide future generations with the ability to meet their needs, taking into account the challenges of climate change and resource depletion. Small homes not only require less energy than larger homes, which preserves natural resources, but they also produce fewer GHG emissions over their life cycles than do larger homes. The average 1,149-square-foot home produces fewer than 450,000 kgCO2e of GHG emissions over its lifetime, whereas the average 3,424 square foot home produces more than 900,000 kgCO2e of GHG emissions. Although the impact of individual GHG emissions varies, reducing the volume of these emissions is important because they contribute to climate change. Because reducing the size of housing has the potential to increase affordability; decrease GHG emissions and energy use; and promote compact, walkable communities, Fifield argues that small, energy-efficient homes should be a part of communities’ plans to promote sustainable development.

Source:

United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development. 1987. Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 43. In: United Nations. 2010. “Sustainable Development: From Brundtland to Rio 2012.” Accessed 23 June 2016; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. 2013. “Measuring the Costs and Savings of Aging in Place,” Evidence Matters (Fall), 11. Accessed 15 June 2016; Michael Fifield. 2016. “Smaller Residential Unit Design Principles as a Key to Sustainability,” American Institute of Architects Convention, Philadelphia, 20 May.

×Source:

Michael Fifield. 2016. “Smaller Residential Unit Design Principles as a Key to Sustainability,” American Institute of Architects Convention, Philadelphia, 20 May; Urban Land Institute. 2014. “The Macro View on Micro Units,” 4. Accessed 4 August 2016; National Association of Home Builders. 2006. “Housing Facts, Figures and Trends,” 14. Accessed 15 June 2016; U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. 1976. “Characteristics of New Housing: Construction Reports C25-75-13,” 37. Accessed 15 June 2016; U.S. Census Bureau. 2016. “Characteristics of New Single-Family Houses Completed: Square Feet (includes Med/Avg Sqft. and Med/Avg Sqft. by Financing).” Accessed 15 June 2016.

×Source:

Michael Fifield. 2016. “Smaller Residential Unit Design Principles as a Key to Sustainability,” American Institute of Architects Convention, Philadelphia, 20 May; U.S. Census Bureau. 2004. “America’s Families and Living Arrangements: 2003,”4–5. Accessed 15 June 2016; U.S. Census Bureau. 2016. “Table H1. Households By Type And Tenure Of Householder For Selected Characteristics: 2015,” 2015 Current Population Survey: America’s Families and Living Arrangements. Accessed 15 June 2016; U.S. Census Bureau. 2016. “Table F1. Family Households, By Type, Age Of Own Children, Age Of Family Members, And Age, Race And Hispanic Origin Of Householder,” 2015 Current Population Survey: Families and Living Arrangements. Accessed 15 June 2016.

×Source:

Michael Fifield. 2016. “Smaller Residential Unit Design Principles as a Key to Sustainability,” American Institute of Architects Convention, Philadelphia, 20 May.

×Source:

Michael Fifield. 2016. “Smaller Residential Unit Design Principles as a Key to Sustainability,” American Institute of Architects Convention, Philadelphia, 20 May.

×Source:

Michael Fifield. 2016. “Smaller Residential Unit Design Principles as a Key to Sustainability,” American Institute of Architects Convention, Philadelphia, 20 May.

×Source:

Michael Fifield. 2016. “Smaller Residential Unit Design Principles as a Key to Sustainability,” American Institute of Architects Convention, Philadelphia, 20 May.

×Source:

Michael Fifield. 2016. “Smaller Residential Unit Design Principles as a Key to Sustainability,” American Institute of Architects Convention, Philadelphia, 20 May; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2016. “Causes of Climate Change.” Accessed 16 June 2016; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2016. “Overview of Greenhouse Gases.” Accessed 16 June 2016; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. n.d. “Resource Consumption.” Accessed 16 June 2016; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2016. “Future Climate Change.” Accessed 16 June 2016; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. 2013. “Measuring the Costs and Savings of Aging in Place,” Evidence Matters (Fall), 11. Accessed 15 June 2016.

×PD&R Leadership Message Archive

International & Philanthropic Spotlight Archive

Spotlight on PD&R Data Archive

Publications

Collecting, Analyzing, and Publicizing Data on Housing Turnover

Resilience Planning: What Communities Can Do to Keep Hazards from Turning into Disasters

Cityscape: Volume 26, Number 3

Case Studies

Case Study: Former School in Charleston, South Carolina, Transformed into Affordable Housing for Seniors

Case Study: Avalon Villas Combines Affordable Housing and Services for Families in a Gentrifying Phoenix Neighborhood

The contents of this article are the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development or the U.S. Government.

Note: Guidance documents, except when based on statutory or regulatory authority or law, do not have the force and effect of law and are not meant to bind the public in any way. Guidance documents are intended only to provide clarity to the public regarding existing requirements under the law or agency policies.