Exploring Racial Segregation and Income Inequality

Patterns and Relationships

Geographic information systems (GIS) allow policymakers to analyze data that is referenced to a geographic location. Part of what makes GIS useful is its ability to both analyze and display data at various geographic scales (neighborhood, municipality, and county levels, among others) and to highlight patterns among interacting social, economic, and environmental variables. Information can be layered and presented simultaneously, to uncover expected and unexpected relationships among various phenomena. In a two-part series in Cityscape (volume13, numbers 2 and 3), Ronald Wilson, a social scientist for HUD’s Office of Policy Development and Research, demonstrates how advanced GIS methods can improve our understanding of complex social and economic issues to guide place-based policy. This type of analysis is particularly important for public policy as it relates to racial segregation and the concentration of minority populations in areas that lack access to good education and economic opportunities, as well as other services. Wilson demonstrates how racial segregation and income inequality can be examined in a comparative context to bring new meaning to the data and underlying relationships.

Analyzing Segregation in a Comparative Context

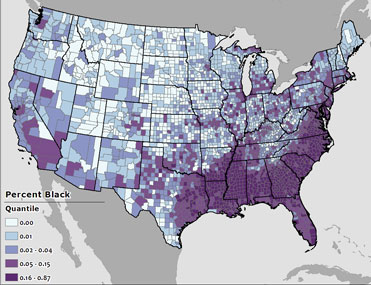

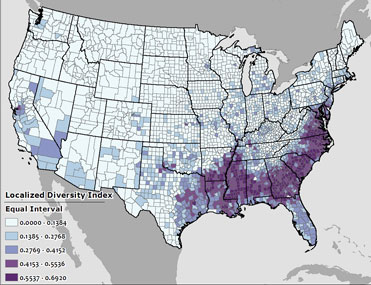

A common approach to analyzing racial or ethnic segregation patterns is to display the population percentage of a single racial or ethnic group in a thematic map (Exhibit 1). While this method is most often used to highlight a pattern, it can misrepresent the data and does not address the racial composition of the remaining population leaving much to be inferred about the relative degree of segregation in a community. Wilson’s analysis highlights a method used to measure segregation with a localized diversity index. The diversity index measures racial segregation and integration, or diversity, at the regional level based on variation within jurisdictions. This approach compares the population of Whites and Blacks relative to each other and uses local data to measure jurisdictional diversity relative to the total population of both groups, thus allowing a national picture of regional segregation patterns within jurisdictions to emerge. The diversity index values mapped in Exhibit 2 show that pockets of segregation are now visible within southern states, with jurisdictions displaying varying degrees of diversity. This creates a marked contrast with the single-proportion thematic map (Exhibit 1), which portrays much of the south as having a large proportion of the Black population. The map in Exhibit 2 also demonstrates how much of the United States remains highly segregated.

Exhibit 1: Distribution of the Black Population for the

Contiguous 48 States - Quantile Classification

Exhibit 2: Localized Diversity Levels of Cities and Counties - Equal Interval Classification

Exhibit 1 illustrates the challenge of using single-population proportion thematic maps to analyze segregation. The map overstates the extent of the Black population throughout much of the country; despite that the majority of the population is located in only 8 percent of the nation’s jurisdictions.

Exhibit 2 presents a more straightforward image of segregation through the use of a local diversity index.

Source: Ronald E. Wilson, “Visualizing Racial Segregation Differently — Exploring Changing Patterns from the Effect of Underlying Geographic Distribution,” Cityscape 13(2), 165.

Exploring Relationships Between Racial Segregation and Income Inequality

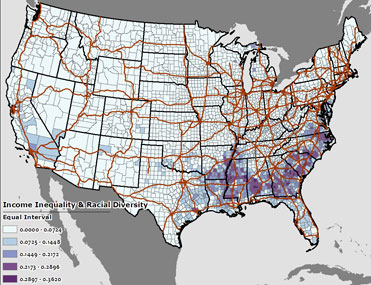

In the same way that the diversity index can measure segregation patterns, an income inequality index can measure income disparity within jurisdictions. In part two of the Cityscape series, Wilson uses an income inequality index based on the proportion of aggregate income derived from net earnings, income maintenance, and unemployment benefits. Because the indexes are derived from the same statistical measures, they can be multiplied to determine how income inequality relates to racial segregation within jurisdictions. High values (approaching 1) from the interaction indicate a racially integrated population with a significant portion of income coming from government assistance. Low values (approaching 0) indicate either a low proportion of Blacks relative to Whites, a county with most of its income derived from net earnings, or both.

The U.S. highway system presents significant regional economic opportunities. In the south, areas with high-income inequality and a significant Black population are often isolated from these regional transportation systems.

Source: Ronald E. Wilson, “Visualizing Racial Segregation Differently —Exploring Geographic Patterns in Context,” Cityscape 13(3), 220.

Based on this analysis, it’s evident that income inequality and regional segregation patterns are concentrated primarily in the South (Exhibit 3). This suggests that while income inequality exists throughout the nation, it is more likely in the south to be associated with racial segregation. Exhibit 3 also includes an overlay of the U.S. highway system; the map shows that many of the areas with high income inequality and high proportions of the Black population are located relatively far from regional transportation systems and the economic development opportunities these networks provide.

Wilson’s analysis highlights the benefit of using advanced GIS methods in framing public policy. The development of local diversity indexes for both racial segregation and income inequality provides a better understanding of local conditions in a regional context, and combining these indexes shows the relationship between the social and economic factors. The example used by Wilson in the articles suggests that policies in the rural south may need to address both racial segregation and economic development simultaneously, and speaks to the larger need to develop place-based policies through rigorous, geographic analysis. Moreover, the articles highlight the need for GIS analyses that incorporate multiple, contextual variables to uncover underlying patterns and relationships among contributing social, economic, and environmental factors.

PD&R Leadership Message Archive

International & Philanthropic Spotlight Archive

Spotlight on PD&R Data Archive

Publications

Collecting, Analyzing, and Publicizing Data on Housing Turnover

Resilience Planning: What Communities Can Do to Keep Hazards from Turning into Disasters

Cityscape: Volume 26, Number 3

Case Studies

Case Study: Former School in Charleston, South Carolina, Transformed into Affordable Housing for Seniors

Case Study: Avalon Villas Combines Affordable Housing and Services for Families in a Gentrifying Phoenix Neighborhood

The contents of this article are the views of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development or the U.S. Government.

Note: Guidance documents, except when based on statutory or regulatory authority or law, do not have the force and effect of law and are not meant to bind the public in any way. Guidance documents are intended only to provide clarity to the public regarding existing requirements under the law or agency policies.