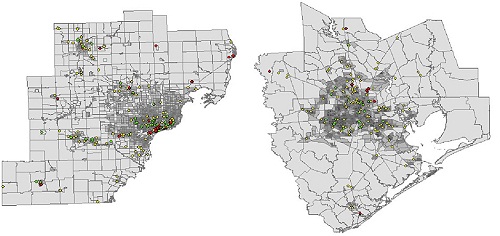

Source: HUD LIHTC Database; 2000 U.S. Census, SF1. Dots indicate the location of LIHTC properties. Red dots are those within local clusters; yellow dots are those exhibiting local patterns of dispersion; and green dots are those exhibiting a random spatial pattern. Census tract population density shown in gray, with low to high population density represented by light to dark gray.

Since its inception in 1986, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program has successfully increased affordable housing production in the United States. The federal program awards a limited number of tax credits to state housing finance agencies, which in turn award the credits to developers of qualified projects, typically those that produce housing that is affordable to low-income households. Although the U.S. Department of the Treasury administers the program, HUD maintains an extensive geocoded database of completed LIHTC projects dating back to 1987. The database contains attributes of each project, including the year the project was built, the number of units, and the percentage of units dedicated to low-income individuals. This information can be mapped and analyzed using a geographic information system (GIS) to understand the location of LIHTC projects and the characteristics of their neighborhoods.

Government officials, researchers, and practitioners are showing significant interest in the siting of LIHTC projects and the degree to which the location of these projects helps meet HUD’s goals. States also influence the location of projects through plans that establish the basis for allocating tax credits; these plans vary by state. For example, some states award points to projects based on their proximity to public transportation, whereas others do not.

Recent research from HUD’s Assisted Housing Research Cadre used the LIHTC database to explore the geographic distribution of projects within 10 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs). The goal was to determine whether LIHTC projects are more densely clustered than housing units are in general, and to understand the neighborhood characteristics of areas where LIHTC clusters are found. LIHTC data were analyzed in combination with GIS measures of the spatial distribution of projects to compare them with a computer-generated pattern that represented the random distribution of housing units within the census tracts that host LIHTC projects. The research shows that across all 10 MSAs studied, LIHTC projects are more densely clustered than in the random housing patterns used for comparison. This clustering revealed that LIHTC properties tend to be located in closer proximity to one another (within 5 miles).

Within the individual MSAs studied, New York had the largest percentage (71 %) of properties classified as clustered, Houston and Dallas had the fewest at 13 and 16 percent, respectively. Houston also has the least clustering of properties in the central city, a finding that highlights the important role that state requirements may play in the location of LIHTC projects. For example, Texas does not allow LIHTC projects to be located within a mile of one another, and the state has prioritized its tax credit awards to projects in suburban rather than central city census tracts.

The research highlights the role that federal incentives for developing in particular areas may play in the clustering of LIHTC projects, and suggests that changing the incentives structure for LIHTC tax credit allocations could potentially affect where projects are built in the future.

BACK TO THE TOP

There is little evidence that relocation by Housing Choice Voucher participants to a new neighborhood increases crime.

The August 2008 Atlantic Monthly article, “American Murder Mystery” by Hanna Rosin, brought considerable attention to housing mobility programs as it implicated HUD’s Housing Choice Voucher Program (HCV) as the cause of rising crime rates in the suburban United States. Rosin relies largely on anecdotes from law enforcement officials and local residents in conjunction with interviews with criminologists and housing policy experts to support her claims. Despite Rosin’s assertions, there is little empirical evidence of a causal relationship between the relocation — and subsequent concentration of HCV participants — and an increased incidence of neighborhood crime.

In partial response to the claims presented by Rosin, HUD sponsored the study “Memphis Murder Revisited: Do Housing Vouchers Cause Crime?” as part of the Assisted Housing Research Cadre. Using crime and HCV data from 10 U.S. cities over a 14-year period, the researchers examined the effect of HCV participant relocation on neighborhood crime rates. Given the claims in Rosin’s article, it could be expected that neighborhood crime would increase as the number of residents using housing vouchers in the neighborhood increased.

Although the initial result showed a positive correlation between an increase in HCV residents and neighborhood crime rates, it did not support the causal effect suggested by Rosin’s article when the impact of broader temporal and city trends was evaluated. When general crime trends were taken into account, the impact of HCV participants on neighborhood crime rates was significantly reduced. Moreover, the research suggests that HCV residents are relocating to neighborhoods where crime is already on the rise, but they themselves are not the cause.

While the evidence presented in the study is preliminary, it does begin to counter the most controversial elements of Rosin’s article. Moving forward, there is a need for further research examining the relationship between HCV participants and neighborhood crime rates. Studies that focus on smaller spatial units that capture more neighborhood diversity could be particularly useful.

BACK TO THE TOP

A demographic shift is underway in the United States. By 2040, the number of seniors (65 and older) will have doubled from 40 to 81 million — or from 13 to 20 percent of the resident population. A large majority of adults prefer to stay in their own home throughout their retirement, owing to the desire to remain independent, the comfort afforded by familiar surroundings, and in many instances, the costs associated with nursing home and other elder care facilities. Researchers and policymakers are assessing strategies that will make aging in place possible.

On average, elderly tenants remain in assisted housing until they reach age 78, but 27 percent stay until they are 85.

Credit:

CDC/Dawn Arlotta and Cade Martin, photographer

To form a basis for helping HUD-assisted elders to age in place, HUD sponsored a preliminary study that examines the demographics of those leaving assisted housing. Researchers determined the average age of elderly residents who departed assisted housing, as well the proportion that stayed until 85 years of age or older, across all HUD programs, regions, household types, and neighborhood poverty levels. Finally, they reviewed the literature for best practices on aging in place and identified meaningful and effective ways to empower seniors to put off entering long-term care facilities in favor of remaining safely in their homes.

Results

Although elderly tenants in assisted housing remained in their homes until they reached an average age of 78, a sizeable 27 percent did not leave their homes until age 85 or older. Their reasons for leaving are unknown, although the literature indicates that some 33 percent of people in long-term care facilities are not “frail elderly.” These individuals enter long-term care institutions before absolutely necessary because they lack the resources to pay for assistance with housework, financial management, cooking, shopping, getting dressed, walking, eating, or bathing.

Additional findings indicate that the amount of time residents remain in assisted housing varies across the programs, regions, neighborhoods, and household characteristics examined, although more research is required to ascertain the reasons.

- The departure age varied by program type; the portion that stayed until at least 85 was lowest in voucher programs (21%) and highest in other assisted multifamily housing (30%).

- The average age at which people left their homes varied by region, with 31 percent of New England residents leaving subsidized housing at ages 85 and older compared with 21 percent in the Southwest.

- A higher percentage of women than men stayed in their homes until at least age 85 (30% and 16% percent, respectively), as did higher rates of whites (32%), compared with blacks (19%) and Hispanics (20%).

- A smaller percentage of disabled households (13%) stayed in place at least until age 85 compared with nondisabled (30%) households.

- People who lived in housing occupied mostly by other seniors appeared to remain in their homes several years longer than average, even in higher poverty neighborhoods.

- The lower a neighborhood’s poverty level, the older the residents were before leaving their homes. In low-poverty areas the average age before leaving was 79 compared with age 76 in high-poverty areas. Of those who did not leave until at least age 85, 32 percent were from low-poverty areas compared with 19 percent from high-poverty areas.

Strategies To Help Keep People in Their Homes

This exploratory study also reviewed the research on strategies that help elderly people age in place. A key factor that empowers seniors to stay in their homes is accessible, quality support services. Simple home modifications, such as ramps and widened doorways for wheelchairs, bathroom aids, and nonslip floors, also help people stay in their homes. Functioning elevators and accessible public transit, which help maintain independence, are also critical to helping people age in place.

Researchers identified a number of effective programs as models, including HUD’s Service Coordinator Program and PACE (Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly), the Medicaid and Medicare initiative that provides home support services to enable seniors eligible for nursing homes to remain in their own housing.

Conclusion

Low-cost interventions such as home modifications may allow seniors to remain safely and comfortably in their homes. Providing services along with housing may be one way to effectively and efficiently support aging in place. Further research on where people go after they exit, and the reasons that elderly persons leave HUD-assisted housing, is necessary. Also needed is an analysis of evidence to learn why some forms of federal housing assistance do a better job of facilitating aging in place than others. Baseline assessments of residents’ needs would also help determine how best to target resources that enable aging in place.

1 Grayson K. Vincent and Victoria A. Velkoff, "The Next Four Decades: The Older Population in the U.S., 2010 to 2050," Current Population Reports P25-1138, 2010.

2 The data came from HUD’s administrative records for the 1.4 million assisted households headed by people 62 years old and older who left HUD-assisted housing programs between 2000 and 2008. These records merely record exits, but not the destinations of those who left. Program types surveyed included Section 202, Section 811, and other assisted multifamily, public housing, and voucher programs. To obtain neighborhood poverty levels, investigators looked to data from the 2000 Census. Neighborhood poverty rates were defined as low (less than 10 percent), medium (10 to 40%), and high (over 40%).

BACK TO THE TOP

|