- Paired testing is a critical methodology for assessing discrimination in the

housing market for both research and enforcement purposes, but it has

some limitations.

- The 2012 Housing Discrimination Study found fewer cases of overt

discrimination since 1977 (when the first such study was conducted), but

other increasingly subtle forms of discrimination against minority homeseekers

persist in both the rental and sales markets.

- A complementary HUD study has found evidence of housing discrimination

against gay and lesbian homeseekers, and forthcoming studies will report

on housing market discrimination based on source of income and against

families with children, persons with physical disabilities, and persons with

mental disabilities.

As federal, state, and local government

agencies and advocacy

organizations continue to confront

the shifting challenges of housing

discrimination, research to understand

the extent of the problem has become

essential to developing successful

enforcement strategies and educational

campaigns. Many researchers and

institutions have contributed to the

body of knowledge on this topic, but

the most significant efforts have been

HUD’s Housing Discrimination Studies

(HDS), especially the national housing

market studies that have been produced

roughly every 10 years since the

late 1970s and which rely on a paired testing

methodology to assess the

incidence of discrimination in the housing

search process. This article discusses

paired testing’s benefits and limitations,

the results of the most recent HDS and

changes over time, and other current

and forthcoming research that will

illustrate the level of discrimination in

the American housing market.

Much of the research into housing

discrimination, including HUD’s HDS,

relies on paired testing, a methodology

in which two testers assume the role of

applicants with equivalent social and

economic characteristics who differ

only in terms of the characteristic being

tested for discrimination, such as race,

disability status, or marital status. Depending

on which part of the housing

transaction process is being tested, the

matched candidates may only request

appointments from housing providers,

or they may visit in person. Although

fair housing groups have used paired

testing to investigate cases of reported

discrimination since the 1960s, the federal

government substantially expanded

use of the methodology for research

purposes.1 When used in fair housing

enforcement, paired testing’s strength

is its ability to flexibly respond to the

circumstances of an individual complaint

(see “Fair Housing Enforcement Organizations

Use Testing To Expose Discrimination”). In the context of research, however,

paired testing requires rigorously

consistent protocols and representative

sampling to yield generalizable

results about the prevalence of housing

discrimination at the national or metropolitan

level.2

Although paired testing has become

an essential methodology for assessing

levels of discrimination, researchers

also note its limitations. Because race

(or another characteristic being tested

for discrimination) cannot be randomly

assigned, these studies do not have a

true experimental design; in addition,

because the auditors are usually aware

of the study’s purposes, “unobserved

characteristics of the auditor, including

their own expectations of discrimination,

may become confounded with

the experimental variable of race,” according

to Massey and Blank.3 Studies

such as HDS address this issue through

tester training that promotes rigorous

adherence to standardized interview

protocols. In housing discrimination

investigations, paired testing cannot

be applied to all portions of the

transaction process; testing protocols

cannot legally include the submission

of fraudulent information in a rental

or loan application to examine bias at

the final transaction point, and discrimination

against current tenants or

homeowners cannot be tested through

this methodology because the characteristics

of the residents are already

known to the provider.4 In addition, the

use of unambiguously qualified candidates

and matched characteristics in

paired-testing studies does not reflect

the reality of systematic racial differences

in income in the United States,

as the average incomes assigned to

minority testers are higher than those

of minority homeseekers in most housing

markets.5 The authors of the 2012

HDS argue that these last two factors

lead to results that could understate the

amount of discrimination in American

housing markets.

Reprinted with permission from the Urban Institute.

Source: Margery Austin Turner, Rob Santos, Diane Levy, Doug Wissoker, Claudia Aranda, and Rob Pitingolo. 2013. “Housing Discrimination Against Racial and Ethnic Minorities 2012,” Urban Institute for HUD’s Office of Policy Development and Research, xi.

There have been four national HDSs,

released in 1977, 1989, 2000, and 2012.

Although the studies have consistently

employed paired-testing methods, the

scope of the studies has expanded and

the focus has shifted with each edition;

the first study focused only on discrimination

against blacks, the 1989 study

added discrimination against Hispanics,

and the 2000 study was designed explicitly

to measure changes in discrimination

patterns over time and included smaller

studies to estimate levels of discrimination

against Asians and Native Americans.6

The most recent study, “Housing Discrimination Against Racial and Ethnic Minorities 2012” (HDS 2012), has samples designed to produce estimates of housing discrimination against blacks, Hispanics, and Asians in the national housing market and also includes estimates of black and Hispanic rental discrimination for a subset of major metropolitan areas.7

As the most recent large-scale study on the topic, HDS 2012 likely gives the most comprehensive view of the current state of housing discrimination against well-qualified blacks, Hispanics, and Asians in the United States. This study, however, provides a conservative, lower-bound estimate of the average measure of housing discrimination in the nation. The study involved 8,047 paired tests across 28 metropolitan areas: 4,838 in the rental market and 3,209 in the sales market. Sales tests were conducted in similar numbers for each minority group; however, rental tests using black and Hispanic testers were conducted more frequently than those using Asian testers for the purpose of assessing metropolitan-level discrimination against black and Hispanic renters in eight sites each. Because random factors besides discrimination can lead to differences in treatment between white and minority testers, HDS 2012 tests both the gross measure of discrimination — the share of tests in which the white tester was favored over the minority tester — and the net measure, which subtracts the share of tests in which the minority tester is favored over the white tester from the gross measure. The authors of HDS 2012 place greater emphasis on the net measure; as they state, “Analysis from the past 25 years strongly suggests that gross measures reflect a lot of random differences in treatment, and that net measures more accurately reflect the systematic disadvantages faced by minority homeseekers.”8 As noted previously, however, net measures can understate overall levels of housing discrimination.

HDS 2012 assesses differences in treatment at multiple steps in the rental housing

inquiry process, and testers record the results of the following questions:

Is the homeseeker able to make an appointment to meet with an agent? If an appointment has been made,

is the homeseeker told that at least one unit is available?

• How many units are available? If units are available,

• What rent is quoted?

• Is the homeseeker shown available units?

• How many units are shown?

• How helpful is the agent (increasingly insignificant as a measure of discrimination)?9

Questions asked in the sales market are largely the same but also consider the racial and ethnic composition of the tracts where homes are shown to assess whether the agent is “steering” the homebuyer toward or away from certain neighborhoods.10

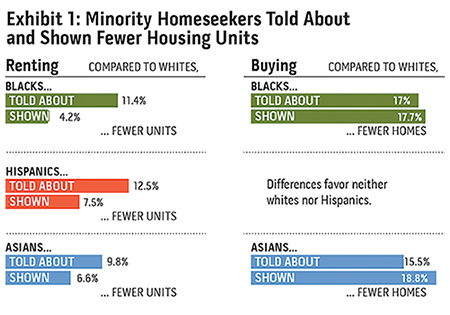

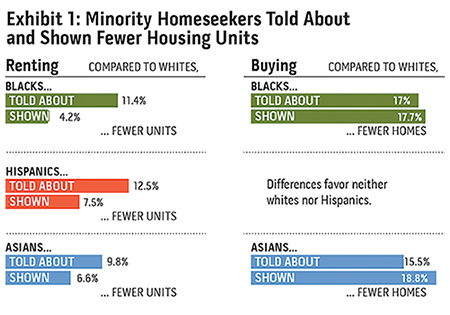

Overall, HDS 2012 shows fewer cases of overt discrimination. Well-qualified minority testers are rarely denied appointments outright, and “when renters meet in person with housing providers, they are almost always told about at least one available unit.”11 Nevertheless, statistically significant forms of discrimination remain in both the rental and sales markets. Rental tests conducted for HDS 2012 reveal the following:

White testers were 9 percentage points more likely to be told about more available units than were black testers, yielding about 0.2 fewer available units per test in aggregate. White testers were also more likely than black testers to be offered a lower rent (although the difference is very small), told about rent incentives, and told that fees and security deposits are negotiable. Agents were more likely to ask black testers questions about their credit standing.12 -

White testers were slightly more likely than Hispanic testers to be told that a unit is available and nearly 13 percentage points more likely to be told about more available units, resulting in white testers learning, on average, about 0.22 more units per visit than their Hispanic counterparts. As with black testers, white testers were more likely than Hispanic testers to be offered a slightly lower rent and to be informed about rent incentives and negotiable deposits.13

White testers were nearly 9 percentage points more likely than Asian testers to be told about more available units, causing whites to learn about 0.17 more units per visit than did Asians. White testers were also more likely than Asian testers to be told about rent incentives and the negotiable nature of deposits.

Compared with white testers, well-qualified black and Asian testers in the sales market were told about and shown fewer available homes and received less information and assistance. Black testers were also 2.4 percentage points more likely to be denied an in-person appointment. The effect of these forms of discrimination is that black homebuyers were told about 17 percent fewer homes and were shown almost 18 percent fewer homes than white testers were, and Asian homebuyers were told about 15.5 percent fewer homes and shown almost 19 percent fewer homes than white testers were. By contrast, the differences between white and Hispanic testers were not statistically significant.14 When shown homes, white testers were more likely than Hispanic testers to be recommended to neighborhoods with a higher proportion of white residents, although the difference was not statistically significant.15

HDS 2012’s metropolitan area estimates of discrimination against black and Hispanic renters did not find significant differences in the rate or severity of discrimination based either on the metropolitan area’s geographic location or its local economy.16 The study did, however, find that renters who could more easily be identified as black or Asian at the phone or email inquiry stage, based on name or speech, were more likely to be treated adversely than those perceived to be white.17

Comparisons between HDS 2012

and previous editions are somewhat limited for various reasons. Technological advances since 2000 have substantially changed the way people search for housing, and testing protocols have had to adapt to match. In addition, housing market conditions following the foreclosure crisis are considerably different from those at the time of the last HDS in 2000, which may have altered other conditions for homebuyers.18 The authors of HDS 2012 note several small changes from the 2000 study, but most are not statically significant; one exception is that Hispanics “are less likely to be denied financing help than a decade ago.”19 HDS 2000, by contrast, was designed to be compared more directly with previous studies. Using a slightly more conservative measure of housing discrimination than HDS 1989, HDS 2000 found substantial reductions in the incidence of discrimination against blacks and Hispanics. Black testers faced less discrimination in both the rental and sales markets than they did in 1989, as did Hispanic testers in the sales market.20 HDS 2000 also revealed that Native Americans faced even higher rates of rental market discrimination than did other minority testers in the three metropolitan areas that included Native American testers, with a net measure of adverse treatment in 18 percent of tests compared with 8 percent for blacks, 14 percent for Hispanics, and

4 percent for Asians.21

These studies demonstrate that the cumulative effect of these differences increases the burden on minority households seeking housing. They also illustrate the more subtle ways in which housing discrimination endures in an era of less explicit racial hostility.

Although the national HDS has long been HUD’s biggest contribution to research on discrimination in the U.S. housing market, the agency has also commissioned other research to supplement the broader studies. The Fair Housing Act does not include sexual orientation or gender identity among its protected classes, although some states have added their own protections (see “Expanding Opportunity Through Fair Housing Choice”). HUD’s “Estimate of Housing Discrimination Against Same-Sex Couples,” published in June 2013, complements the national HDS by examining the experiences of same-sex couples in the rental market using internet searches and email solicitations of interest.22,23 Researchers conducted 6,833 matched pairs tests across 50 randomly selected housing markets; about half of the tests compared the treatment of gay couples with that of a heterosexual couple, and half compared the treatment of lesbian couples with that of a heterosexual couple.24 As with the HDS studies, researchers calculated both gross and net measures of discrimination.

Joseph and Lauretta Codrington pose next to their picture from 1992, when the Fair Housing Center of Southeastern Michigan helped the couple settle a housing discrimination case. Photo courtesy: Kristen Cuhran, The Fair Housing Center of Southeastern Michigan

The study found that, in gross measures, heterosexual couples were significantly more likely than either gay or lesbian couples to receive responses to email queries; according to the authors, “heterosexual couples were favored over gay couples in 15.9 percent of tests and over lesbian couples in 15.6 percent of tests.”25 Net measures of discrimination were smaller and were statistically significant only for gay couples. Discrimination was present in all markets tested, but no clear connection existed between the level of discrimination and market size. States with legislative protections against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity (21 states and Washington, DC, at the time of the study) actually showed slightly higher levels of adverse treatment for gay and lesbian couples. The authors theorize that this finding could be the result of low levels

of enforcement, housing providers

not understanding local laws, or “the possibility that protections exist in states with the greatest needs for them.”26 Overall, the authors argue that the discrimination observed in the study probably understates the actual level of discrimination in the rental housing market because the study examined only the first step of the rental transaction. A forthcoming HUD report will incorporate in-person testing that could give a better estimate of the scale of the problem; this study will also analyze discrimination against transgender Americans.

Other upcoming studies will report on housing market discrimination against families with children, persons with physical disabilities, and persons with mental disabilities as well as discrimination based on source of income

— principally to assess the degree of discrimination against those who pay for housing with vouchers. These reports will further expand HUD’s critical role in funding research that lays bare the current state of housing discrimination in the United States and helps guide the efforts of advocates and fair housing enforcers at all levels.

-

Alex F. Schwartz. 2006. Housing Policy in the United States, New York: Routledge, 219; Margery Austin Turner, Todd Richardson, and Stephen Ross. 2007. “Housing Discrimination in Metropolitan America: Unequal Treatment of African Americans, Hispanics, Asians, and Native Americans,” in Fragile Rights Within Cities: Government, Housing, and Fairness, ed. John Goering, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 40.

-

Margery Austin Turner, Rob Santos, Diane Levy, Doug Wissoker, Claudia Aranda, and Rob Pitingolo. 2013. “Housing Discrimination Against Racial and Ethnic Minorities 2012,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research, 3.

-

Douglas S. Massey and Rebecca M. Blank. 2007. “Assessing Racial Discrimination: Methods and Measures,” in Fragile Rights Within Cities, 69.

-

Turner et al. 2013, 3.

-

Ibid

-

Ibid., 1–2.

-

Ibid., 2.

-

Ibid., 4.

-

Ibid., 39.

-

Ibid., 50.

-

Ibid., 39.

-

Ibid., 41–3.

-

Ibid., 45–6

-

Ibid., 51.

-

Ibid., 52.

-

Ibid., xviii.

-

Ibid., 73.

-

Ibid., 2.

-

Ibid., 65.

-

Turner et al. 2007, 47.

-

Ibid., 51.

-

The study examines only the sexual orientation of same-sex couples; other potential sources of discrimination, like gender identity, are not included.

-

Samantha Friedman, Angela Reynolds, Susan Scoville, Florence Brassier, Ron Campbell, and McKenzie Ballou. 2013. “An Estimate of Housing Discrimination Against Same-Sex Couples,” U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research, v.

-

Ibid., v.

-

Ibid., vi.

-

Ibid., vii.

Previous Article

Evidence Matters Home Next Article

|