February/March 2010

In this Issue

Returning Foreclosures to Productive Use with Land Banks

Preventing Foreclosures, One Community at a Time

Fighting Blight Pays in Philadelphia

Resilience Matters in Foreclosure Crisis

In the next issue of ResearchWorks

Fighting Blight Pays in Philadelphia

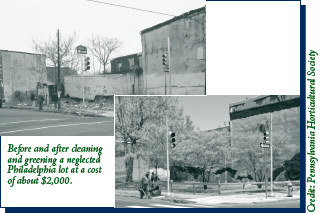

Although urban blight is not a new problem for cities, a significant number of abandoned and vacant properties resulting from foreclosures intensify the incidence and impact of blight and contribute to community destabilization. Local responses include halting the deterioration of abandoned, neglected properties by "cleaning and greening" and with regular maintenance. The city of Philadelphia finds this to be a relatively inexpensive strategy in light of the return, costing $1.50 per square foot to clean and green a lot (about $2,000/lot), and $0.17 per square foot (about $200/lot for 14 cleanups between April and October) for subsequent maintenance.1

Philadelphia has a history of combating property blight with cleanup and greening activities. Significant post-WWII losses of businesses, employment, population, public revenue, property values, and morale left many of the city's neighborhoods with vacant lots and neglected houses. The city's efforts to fight this blight entwine with those of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society (PHS), a nonprofit that promotes the use of horticulture to improve quality of life and create a heightened sense of community. PHS established Philadelphia Green in 1974 to fight neighborhood blight with innovative greening strategies.

Having observed that vacancy creates vacancy, Philadelphia Green's first initiative was to join the city in encouraging residents to plant community vegetable gardens in vacant lots. The organization next teamed up with community development corporations to replace vacant lots with open, green spaces in low-income neighborhoods, including the American Street Neighborhood Empowerment Zone.2 By 1995, Philadelphia Green and the New Kensington Community Development Corporation (NKCDC) were targeting 1,100 vacant lots, 70 percent of which were privately owned and tax delinquent, in a deindustrialized neighborhood where the population had plunged 50 percent during the previous 40 years. Within 4 years, one-third of these lots were cleaned and greened, 108 converted to side yards, and 62 were community garden sites. Community residents and NKCDC were regularly maintaining one-half of these sites.3

With the unveiling of the Neighborhood Transformation Initiative in 2003, the city committed $10 million for a minimum of 5 years and $296 million in bond proceeds toward transforming deteriorated and abandoned properties into clean, green space. Contracting with PHS (who recruited the help of nonprofits, community-based organizations, minority contractors, and other businesses) to help restore neighborhoods, the city stabilized vacant land by cleaning, mowing, laying topsoil, planting seeds and trees, and adding fences. Today, 7 million square feet of vacant land is stabilized and regularly maintained.4

Economic Impact

Economic Impact

In light of the question of whether there is adequate justification for spending public monies on blight removal and greening activities and whether greening is truly effective as a revitalization tool, Susan Wachter and her research team from the Wharton School found a way to measure the impact of vacant land management and greening investments made in Philadelphia.5

These researchers integrated spatial- and time-based data with city property sales information; property attributes for more than 200,000 sales of more than 120,000 properties from 1980 to 2005; data on neighborhood characteristics; and PHS records on the time and location of new tree plantings, streetscape improvements, and vacant lot stabilizations. This database provided the foundation for comparing neighborhood values before and after greening activities by analyzing nearby property sales. It also enabled an assessment of the citywide impact of many variables-as well as of individual neighborhoods-when combined with geographic data and GIS technology.

This research confirms that the physical attributes of a home and neighborhood characteristics do affect home values and sale prices. Of particular interest was whether cleaning and greening activities that eliminate blight are cost-effective. Researchers concluded that "urban greening has emerged as a potentially key land management strategy in Philadelphia." The following findings explain this conclusion:

- The value of homes near businesses and shopping centers benefited from landscape enhancements. Homes near commercial corridors in excellent condition because of such improvements as tree, container, and median plantings; pocket parks; and parking lot screens showed significant gains in value. Residences within a quarter-mile of such commercial greening experienced a boost in value of approximately 20 percent and an increase of about 10 percent within a quarter- to a half-mile. Homes increased in value by 30 percent when located in a business improvement district that provides additional public services.

- Home values were influenced by the condition of adjacent lots. Homes next to vacant, neglected lots dropped in value by approximately 20 percent, whereas homes next to lots that have been stabilized by trash removal, soil improvement, plantings, and other amenities rose in value by about the same amount.

- Planting trees in an urban environment has a significant positive economic effect. Proximity to new tree plantings was associated with an increase in house prices of approximately 10 percent.

This research demonstrates that the return on green investment is measurable, and provides a method by which policymakers can project outcomes. The findings suggest that cleaning and greening can be an effective tool in fighting foreclosure blight without being unduly costly or burdensome, especially when an effective partnership exists between local government and community groups. In addition, the results underscore what people value in their communities and neighborhoods.

Although every community has its unique municipal structures and challenges, Philadelphia Green Director Robert Grossmann stresses the following message for other cities: "Although a city does not own abandoned and neglected properties, it does own the problem. Once owned, creative solutions are possible."

1 Susan M. Wachter, "Greening Vacant Land," presentation at Green Infrastructure Symposium, Pittsburgh, October 25, 2009.

2 J. Blaine Bonham, Jr., and Patricia L. Smith, "Transformation Through Greening," in Eugenie L. Birch and Susan M. Wachter, eds., Growing Greener Cities (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 227-43.

3 Eva Gladstein and Mike Groman, "Vacant Land Management and Community Revitalization Through Greening," presentation at National Vacant Properties Campaign Conference, Pittsburgh, September 24-25, 2007.

4 December 2009 interview with Robert Grossman, director of Philadelphia Green.

5 Susan M. Wachter, Kevin C. Gillen, and Carolyn R. Brown, "Green Investment Strategies: How They Matter for Urban Neighborhoods," in Birch and Wachter, Growing Greener Cities, 316-25.